Menya Goos Naimark and Jacob Naimark

Refuge in Canada

|

Menya Goos Naimark and Jacob Naimark |

|

|

|

|

Turiysk street scene |

In the small town of Turiysk all the Jews kept an eye on each other. This not-so-subtle pressure fostered the keeping of tradition. Each day, there were morning, afternoon, and evening services, which all the males of the community attended. According to Sam:

|

|

|

A translation of a notarized Polish document attesting to Chana Marjam (Miriam) Naimark’s birth in Turiysk in 1916 |

“Menya was an observant Jew. She lit Sabbath candles every week and observed the other traditions. Each year before Rosh Hashanah, she went to the graveyard and visited her father's grave. During the shiva [mourning] period after the death of a close relative, Menya covered the mirror in black. She always washed her hands after returning from a cemetery.

Sam Naimark recalled how Turiysk changed with the times:

"During World War I, Turiysk was occupied by Germans. The soldiers used to steal food from the barracks and gave it to the Jews but not to the Poles or Ukrainians.

|

This postcard was made during World War I, when first the Austrian army and then the German army occupied Turiysk. The caption, written in German, says, “Greeting from Volyn, railroad station.” Volyn is the region in western Ukraine where Turiysk is situated. |

"After the war, Turiysk came under Polish rule. My mother insisted on leaving because of us children—she didn't want her sons to grow up and serve in the Polish army. At seventeen, boys were called up. If you were a sixteen-year-old male, you couldn't even leave the country. When Aaron was sixteen my parents paid some lawyers a lot of money to change the dates of our birth certificates and make all the boys appear to be a year younger. I know I was born in 1912, but on all my papers my birth date is 1913.[1] Once Aaron appeared to be fifteen years, he was allowed to emigrate.

"My mother had always wanted to join her brothers in Chelsea because of the pogroms in Russia and Poland. In 1927, Jacob finally was persuaded. He listened to my sisters, Sara and Devorah [Dora]. Immigration into the United States was then on a quota basis, and it would have taken another ten or twenty years before our family could obtain entry. We were able instead to get papers into Canada. Menya's brothers all chipped in to pay for our passage and we moved to Montreal, it being the Canadian city closest to Boston. Menya brought from Europe her samovar, two silver candlesticks, and a silver Kiddish cup.

"We came over on the Vollendam,

a freighter with few accommodations for passengers. Every one of us was seasick

except for Aaron. He had a job attending to everybody else. Nobody could sleep

and nobody could eat. Most of the time we stayed below deck except to throw up.”

|

|

|

|

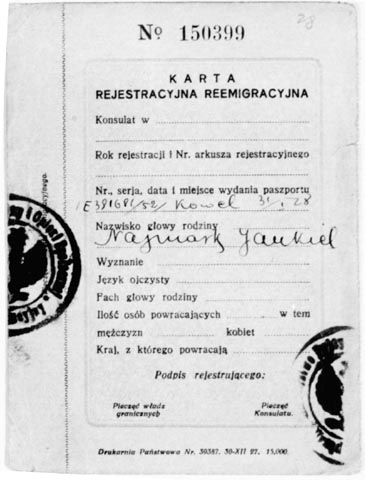

Menya and Jacob used these passports to leave Poland. |

|

|

|

|

Eddie and Henry Naimark, the youngest sons of Menya and Jacob, were able to get an education when the family moved to Canada. The oldest siblings had to work. |

Menya’s brother Morris Gass and his wife Sarah came to Montreal and greeted the Naimarks when they arrived. The first night, Sarah found a home where all ten Naimarks could stay. Within a day or two, she had rented an apartment for them and enrolled the younger ones in school. She went shopping as everybody needed clothing. She also gave all the family members their English names.

In Montreal, with help from his brothers-in-law in Massachusetts, Jacob purchased three newspaper stands, and he and his two oldest sons, Aaron and Sam, went into business. The younger children attended school. During the years that followed Jacob worked at various jobs. Lillian Naimark, Norman's wife, recalls:

"Jacob didn't know the ways here. The boys didn't want to sell newspapers anymore and went on to other things. For a while Jacob went into the brush business. And before that he was in Dependable Slippers. But he had been a farmer in Europe, he ran a mill, he wasn't a businessman. He didn't make a big success of any of the businesses he went into here."

Jacob attended shul regularly. He

paid for one seat for himself but not for his sons so they didn't attend the

high holidays when the shul was filled to capacity. As a reaction, when his

youngest son Henry went to shul as an adult, he always took seats for his own

children.

|

|

|

View of Montreal from the Church of Notre Dame Credit: ©1900. Detroit Publishing Company. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-D4-15494] |

|

|

|

Dominion Square, Montreal Credit: ©1900. Detroit Publishing Company. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-D4-12496] |

|

|

|

|

Place Viger Hotel and Station, Montreal Credit: ©1900. Detroit Publishing Company. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-D4-12499] |

Montreal city hall Credit: ©1900. Detroit Publishing Company. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-D4-12497] |

|

|

|

An ice castle built for Montreal’s Midwinter Carnival, 1909 Credit: ©1909. Keystone View Co. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USZ62-96850] |

Passover at the Naimarks was very traditional. After the first portion was completed and the meal eaten, the boys would disappear from the table and Jacob finished the sedar by himself.

|

|

|

Jacob Naimark at 40. Is this identity document Jacob’s Canadian voter registration card? |

Menya is remembered as a lovely woman, very good-natured and intelligent. She was very motivated to learn to speak and read English, and she anglicized her name, changing it to Minnie. She took English lessons in a Jesuit Church and paid her children to speak English to her. She even taught herself to write.

|

|

|

Menya’s Canadian naturalization certificate |

Despite her interest in the modern world, Menya still clung to some superstitions from the shtetl. She believed 13 was an unlucky number and she tied red ribbons on cribs to keep away the evil eye. If someone would compliment a beautiful or smart child, Menya would say (in Yiddish), Three women sitting on a stone wherever it came from it should go back. Pu-pu-pu.

[1] This may explain discrepancies in dates of other family members as well.