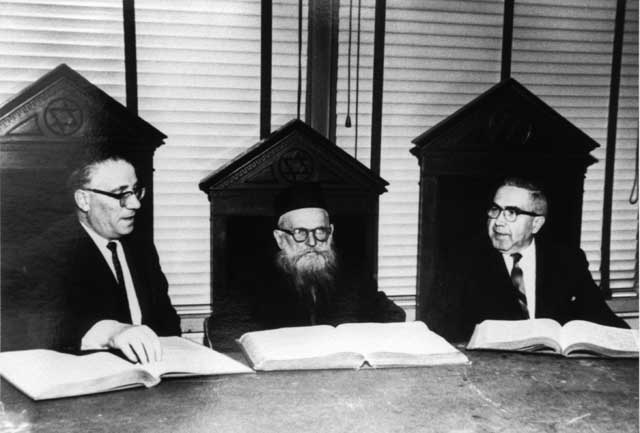

| The Bet Din |

|

|

|

Samuel Korff served on the Bet Din, the rabbinic court in Boston. |

"My father was also a driving force behind the Bet Din, the rabbinical court of justice of the Associated Synagogues,” explained Joseph Korff. “Almost every city has a rabbinical court. The courts tend to be formed by Orthodox rabbis and they deal with religious questions and grant religious divorces. Their focus tends to be supervision of kashrut and Jewish family law. My father, however, broadened the scope of the Bet Din.

An article in the New York Times in February 1973, described the uniqueness of Samuel Korff's Bet Din:

"...until the late 18th and 19th centuries, when Jews began leaving the ghetto. The beth din (house of law) ruled on virtually all legal matters within the autonomous Jewish communities. Then gradually the courts lost their secular legal standing and narrowed their scope to ritual and family matters.

"Today most rabbinic courts...focus on such cases as marriage, divorce, and conversion. But the Massachusetts Rabbinical Court of Justice, of which Rabbi Korff is administrator, is no ordinary beth din.

"Ever since the socially conscious 1960s, the 31-year-old court here has gotten involved in social issues, often outside the Jewish community.... [It] has even settled disputes between gentiles. It tackles issues upon request from individuals or groups and charges no fee. If both parties in a case sign over rights to the court as an arbitration board, the decision is legally binding. Otherwise, the beth din's only enforcement power is "moral persuasion" or public pressure within the Jewish community.

"...From the beginning the Massachusetts court has represented all three branches of Judaism, unlike the other courts around the country, most of which are Orthodox. This arrangement, according to Rabbi Korff, is not problematic.

"When it is asked to judge ritual divorce or other cases that directly involve halacha (Jewish law) only Orthodox authorities sit on the court since neither Conservative or Reform branches observes halacha strictly...Other issues…may be settled by rabbis of any branch, as well as by lay people--lawyers, political scientists, and other experts in various fields—who may or may not be Jewish. But in such cases, the panel does not constitute a beth din in the traditional sense of the word.

"All persons sitting as judges on a given case have equal votes in its outcome. The majority decision prevails; rabbinical courts do not issue dissenting opinions...

"As administrator [Rabbi Korff channeled]

discussion to basic issues, interrupting what he thought to be extraneous

dialogue and drawing conclusions when it seemed that all views have been

expression.

|

|

Samuel Korff at a meeting of Boston’s Bet Din |

"He also softened questions by his colleagues to spare the feelings of witnesses. For example, in a case involving a Greek woman who wished to become an Orthodox Jew, Rabbi Korff interrupted a colleague who was asking her what she would do if she broke up with her Jewish fiancé.

"I wouldn't be that cruel, Rabbi Korff said smiling to the young woman, I would ask if you want to become Jewish irrespective of your status, married or not married.

"...According to the 59 year-old rabbi, a beth din can offer nonsectarian resolutions to all human problems because its concern is justice and justice must transcend a given creed, race, or religion.

"For instance, he said, a tenant leases an apartment and then discovers it has cracks in the wall and holes in the floor. He had already signed a contract, so who is liable?

"Jewish law says the landlord must make every repair, Rabbi Korff concluded. Why? Because no one has the right to sell something that is a receptacle for human misery. So it was safe for the tenant to assume the landlord would be a mensch [a good human being].

"...Responding to a request by students and faculty at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the court in 1970 issued a 54-page document exploring matters of conscience.

"Among other things it supported selective conscientious objection—objection that is to one war, but not all wars—but declined to rule on the legality of the Vietnam War because it had not heard government testimony.

"Although some Orthodox rabbis take a dim view of a beth din that tackles such problems, Rabbi Korff is optimistic that other rabbinic courts will widen their focus of concern soon.

"If the rabbinic court would be restored to its proper position, the rabbi asserted, it would bring a voice on conscience not only to the Jewish community but to the total society." [1]